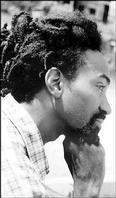

THOMAS GLAVE delivered a reading of his collection of essays Words to Our Now: Imagination and Dissent, published by University of Minnesota Press, at Redbones the Blues Café, recently. Glave is an assistant professor of English at Suny Binghamton in New York. Though born in New York, Glave is of Jamaican descent and he shares his identity between both countries. The collection tackles issues of hatred and prejudice that ranges looking at homophobia, racism in the United States and the war in Iraq. In an intriguing exploration of identity, Glave refers to himself as "a living, breathing oxymoron: a Rasta b...man". In the following interview, he speaks of the collection, prejudice and anti-homosexuality in Jamaica.

THOMAS GLAVE delivered a reading of his collection of essays Words to Our Now: Imagination and Dissent, published by University of Minnesota Press, at Redbones the Blues Café, recently. Glave is an assistant professor of English at Suny Binghamton in New York. Though born in New York, Glave is of Jamaican descent and he shares his identity between both countries. The collection tackles issues of hatred and prejudice that ranges looking at homophobia, racism in the United States and the war in Iraq. In an intriguing exploration of identity, Glave refers to himself as "a living, breathing oxymoron: a Rasta b...man". In the following interview, he speaks of the collection, prejudice and anti-homosexuality in Jamaica.Tanya Batson-Savage: Your earliest piece in this collection, 'Baychester: A Memory' is dated 1994 and there are pieces from 1999, 2000, and 2002 moving through to 2004. Were these essays always conscious parts of a collection?

Thomas Glave: No. I had no idea when I wrote Baychester that it would someday be included in this book. A few of the essays were written as public addresses/lectures, including a talk I did at UWI, Mona. It was only after a relative suggested a few years ago that I would soon have enough material for a book of essays that I began thinking of these works collected together, although around the same time I had begun thinking of assembling an essay collection and had even come up with a title for it a different one than the one I ended up using.

TB: What led to the selection of the title 'Imagination and Dissent'?

TG: That subtitle seemed best to encapsulate what this book embodied: Writing that used language imaginatively, creatively, experimentally, but also forcefully dissented against (for example) human rights violations, the war in Iraq, U.S. foreign policy, the harmful effects of globalisation, etc.

TB: You were born in New York and you now teach there, but much of Words to Our Now is concerned with the state of Jamaican society. How much of your youth was spent in Jamaica?

TG: A great deal of my youth was spent here, starting at a very early age as early as two or three. This isn't unusual; a lot of Jamaican families abroad ensure that their children spend time back 'home'. I was very lucky in that regard. My parents always made sure that I spent extended time with family in Jamaica.

TB: You have described yourself as an in between man, because of your identity which is shared between Jamaica and North America. Is this in betweenness a good or a bad thing?

TG: It's neither good nor bad it just is. It's a kind of hybridity, a new kind of Jamaican identity, one that comes out of both places and moves between both places. I am a diasporic Jamaican, a child of the massive Jamaican diaspora. There are thousands of us, if not millions. In my case, it's all complicated deepened by my homosexuality.

TB: Much of the politics of hatred which you attack surrounds the intolerance of Jamaicans for homosexuality, but you have other politics of hate dealt with in the text. Do you believe all hatred is the same?

TG: All hatred is the same in one sense; hatred always, first and foremost, diminishes the human spirit and possibility of the person who hates. It is a negative, usually destructive force. But people hate differently and for different reasons. Black people everywhere, including Jamaicans, are hated looked down on in much of the world today and so are gay people, Jews, Muslims, and other people. What does this teach us?

TB: Do you believe Jamaica has received fair play in the international press regarding our homophobia? That is, there is much talk about how intolerant we are of homosexuality, but it is usually said in a generalising fashion that suggests all Jamaicans hate homosexuals. However, some would argue that there is an increase in tolerance here. What is your position on this?

TG: It's complicated. Jamaica is, without question, an extremely intolerant, homophobic society. It's high time we stopped trying to dodge this truth and faced it honestly. If we don't, we'll never grow as a people. Very few people in the Jamaican media so far have asked Jamaican homosexuals to talk about how they feel about Jamaican homophobia.

It isn't up to Jamaican heterosexuals to determine how homophobic Jamaica is or is not, since they don't suffer the antigay oppression that those of us who are gay or lesbian suffer. At the same time, I do think that things are beginning to change for the better in Jamaica, although very slowly.

I would like to think that I've seen some significant changes in the middle class, which is the part of Jamaican society I know best, coming from it. Even a few Jamaican ministers and priests in Jamaica have become a little more progressive on the issue. The entire world is changing on the issue and Jamaica will have to move with that change, especially if it wants to avoid becoming truly repugnant to the rest of the modern Western world. It is a sad fact, and a big problem, that a lot of people out there regard Jamaica as a country of backward, ignorant black people who continue to resist inevitable social change.

TB: If you do not agree that there is an increase in tolerance, what do you think can increase tolerance of sexual orientation?

TG: We've never wanted to talk about homosexuality in Jamaica, right? Not unless we are vilifying it or gossiping negatively about it. We need to begin talking about it constructively that is, we have to find ways to make our family and friendship spaces more welcoming to the gay people among us. If we don't, those people will remain hidden and unknown to us and some of those people could be our husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, grandparents, best friends, church members.

TB: What role do you believe the media has to play in stemming intolerance? Do you see signs of this happening?

TG: The Jamaican media, like all media everywhere, needs to become more intelligent and sophisticated in how it discusses the issues. We need less sensationalisation (such as we see often in the Jamaican tabloids) and more in-depth, sensitive reporting. We also need the media to understand that homosexuals do not spend all our lives thinking about sex, any more than heterosexuals do. We are complex human beings, just like you. More interviews like this one, I think, will help.

TB: You have suggested in the past that the literature department at the UWI should "queer" its curriculum.

What role do you believe this has to play in the larger society?

TG: UWI educates people; that is its job. In a university environment, full, complete education means inclusion of all sorts of topics for discussion. We're not doing our work as educators (and I am a literature professor) if we don't expand our curricula. We're also not doing service to gay and lesbian UWI students, and to everyone, if we refuse to add gay and lesbian material to the curriculum.

Also, gay and lesbian courses are being taught in just about every major university in the Western world now. 'Queer Studies' is an expanding field and offers enormous opportunities to Caribbean scholars. UWI risks becoming a second-rate, intellectual joke if it doesn't keep scholarly pace in this regard with other, international universities. That's what university systems should do - inspire each other to grow intellectually.

TB: You describe yourself in 'Following the Body Divided: Hair' as a "Rasta battyman". Is that a case of appropriating the word to rob it of its power? Can such a word be actively appropriated?

TG: It depends on who is using the word. ("Battyman", by the way, is not a word I ever heard anyone in my family use - and I'm sure that none of my family would use that word.) The word can be appropriated if I decide I want to appropriate it - and I did. I like the idea of calling myself a Rasta battyman: I am being a little playful, a little humourous and simultaneously showing that words can indeed be turned around to rob them of their negative power.

TB: You suggest that your hair acts as a mask a sort of protective shield against accusations. Was it a deliberate disguise or a happy circumstance?

TG: It was more of a coincidence. I didn't grow my hair to ward off accusations, in Jamaica, that I was gay. I didn't grow my hair as a 'mask'. But the very fact that I felt concern about being targeted as gay in Jamaica should give you some idea of what we go through all the time as gay people here - the fear and tension we experience, especially since there are virtually no J'can laws to protect us. Yet.

TB: Many lay continuing homophobia on the lips of DJs. Do you believe that this is disproportionate blame and anti-homosexual lyrics are merely a reflection of prejudices which are firmly rooted in the society?

TG: You say 'merely' a reflection; that is a huge 'merely'! I think that DJs have enormous influence among young people and could be singing about more crucial issues in J'can society, following the powerful examples of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, e.g. When we have so much violence, poverty, and injustice, why do the DJs continue to sing about killing homosexuals? Why don't they sing about stopping violence and building communities? Why can't they sing about the benefits of an education and the need to take better care of our children? I'll tell you why; because it's fashionable and profitable to sing about "battyman fi dead" and those songs will sell. These antigay prejudices may be, as you suggest, "firmly rooted" in the society, but no society is cast in stone and every society must either eventually change with the rest of the world or die.

TB: 'Regarding a Black Male Monica Lewinsky, Anal Penetration, and Bill Clinton's Sacred White Anus' tackles the issues of race, sexuality and politics. Do you think the world is at all ready for an openly homosexual leader?

TG: What we call "the world" never seems to be ready for anything until it happens. Was "the world" ready to see Jamaica become an independent nation governed by its own people? I think that, at least in the west, we are more than ready for an openly homosexual leader. Why not? An example: the three-time elected mayor of Cambridge, Massachusetts - the city of Harvard University and MIT - is an openly gay man of Jamaican background Kenneth Errol Reeves. We should, all be very proud of him and be inspired by his 36-year relationship with his partner, Greg Johnson.